Chinese Culture

It is no secret that there are larger and also more subtle differences

between Chinese and European cultures. I hope that the reader does not expect me

to write in a few pages what more savvy people have written in books

thousands of pages thick. What I will attempt here is to state my observations

and thoughts, which may give some clue and reason as to why such differences may

exist.

|

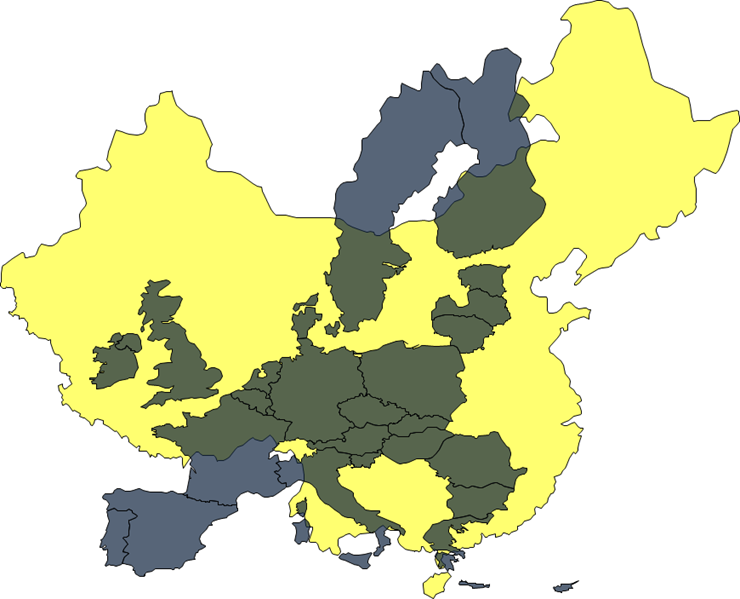

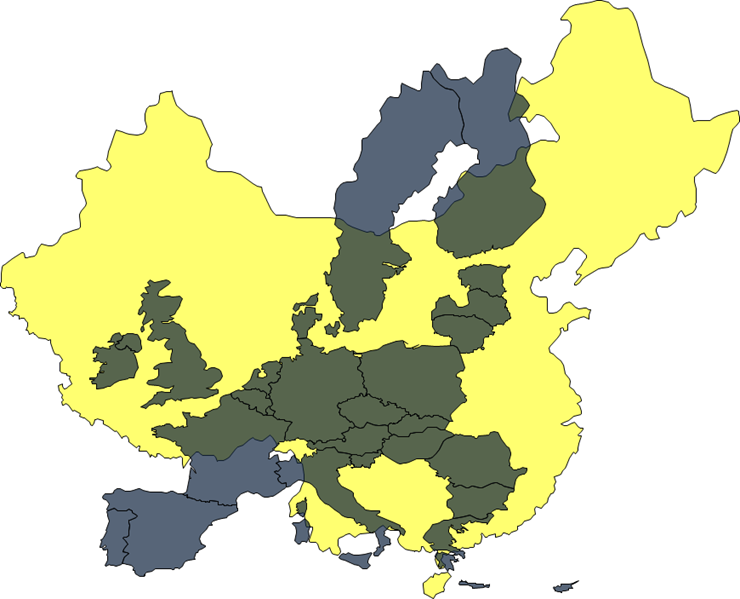

Let us look at the overlaid maps of Mainland China and

Western and Cemtral Europe. Some things are to be noted:- The land area of China is

similar to that area of Europe from Atlantic to the Ural mountains,

including the European part of Russia

- The

east-west extension is also similar to that of Europe from Portugal to

the Ural mountains

- China's northernmost point lies on about the same

latitude as Hamburg, while the latitude of the southernmost point of

continental China is close to that of Khartoum in Sudan

- The population of Mainland China is about three times that of the

EU, and 90% of that population live in the eastern half of the

country, so the average population density there is about three

times that of the EU

- If you compare the geographies, Europe is a very diverse

continent with mountain ranges, peninsulas, and many small-scale

geographic features, having given birth to many diverse

nationalities.

- In China, we see quite few but much larger landscapes: The

fertile lowlands of the east, the mountains of the southwest, and

the largely infertile and desertified lands in the north and

northwest, having facilitated a very early unification of the

country.

|

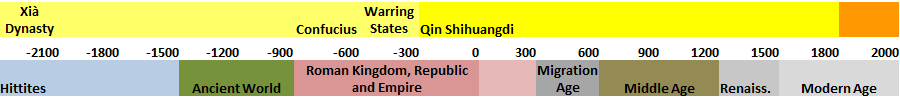

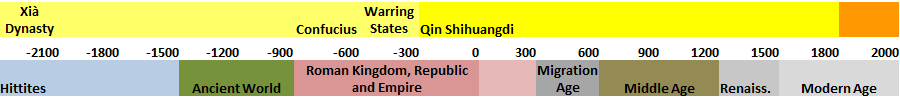

We see a similar pattern when comparing the historic developments in

both regions: European philosophy and thinking is usually traced back to

ancient Greece, with some tales and traditions predating these. The

development of agriculture, cities and states may be traced back to the

Hittites. Moving forward from there until now, we see many breaks and

disruptions in European history, such as the development of Rome from a

small kingdom, and a republic, into an empire. This empire partially

disintegrated, leading to the middle ages in the west while the eastern

part survived and conserved antique thinking until 1453. After the

middle ages, the renaissance (French for re-birth) gave way to the Age

of Enlightenment, which turned into industrialization and finally into

the modern world.

In China on the other hand, we see a very

different development. There were warring states and dynasties, but the

culture has developed in a comparably steady

and unified way. The first written

records of the Chinese history, written in Chinese language, appeared

when the Hittite kingdom flourished. Confuzius (孔子 Kǒngzǐ), whose

teachings influence Chinese and East Asian thinking until today, lived

from 551-479 BC. In Southern Europe, the Greek poleis fought with the

Persian Empire while Northern Europe lived in the pre-Roman

Iron Age

(the Hallstatt culture).

China became a united country for

the first time when Rome fought the second Punic war with Hannibal. |

|

|

你看懂汉字吗?

Another indispensable part of the Chinese culture is the script. A

Chinese character may represent a meaning, a notion or lexeme. Other

characters may represent or indicate a phoneme which sounds similar to

the vocal representation of a different lexeme.

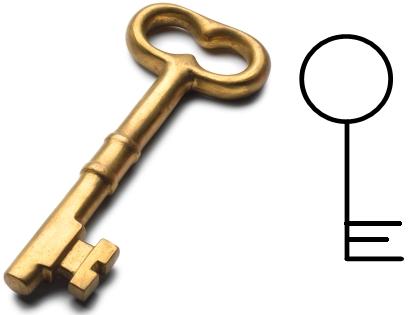

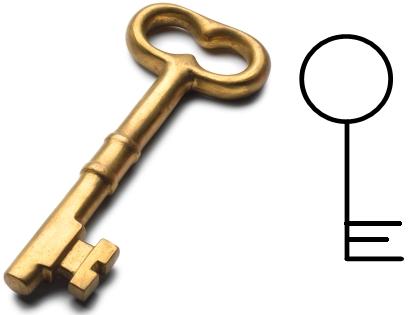

Imagine that we were faced with inventing an ideographic script, i.e.

a script where a symbol represents an idea. As symbol for a key, we

could just draw a simple picture of a key. |

|

Now there is another very different thing which nonetheless we denote

with the same phoneme (i.e. the same vocal representation). We could

invent a new character, or we take a character which represents the

phoneme and add a modifier to indicate the different meaning.

This

modifier is called the radical, and most Chinese characters are made up

that way.

What makes it more complicated is that the spoken language

has changed over time while the script has not changed so much. Imagine

that we would still call a key for a lock a key, but a key on a

keyboard would by nowadays be called a knob. Then the character

would be the same, but not give us any hint how it is spoken. |

As a character represents a lexeme (loosely speaking, a thing or a notion),

which in turn is represented by a phoneme in speech (i.e. it is spoken in some

way), the Chinese script can only represent words (better speaking, syllables)

of the Chinese language. If your foreign name contains syllables which are not

part of the Chinese language, then your name cannot be written in Chinese

characters. There is no way to spell "Peter" in Chinese.

All you can do is one

of two things: Either you choose some Chinese word which sounds similar to your

name (the phonetic translation), or you find the meaning of your name and use

the Chinese word for that name.

An example for the phonetic translation is the Chinese name of Siemens.

Siemens is a German surname (obviously the founder's) but has no special

meaning. The Chinese name is 西门子 - Xīménzi. That sounds similar to "SEAman-DZE!" and not too far from the German pronunciation.

An example for the semantic way is the Chinese name of VW (Volkswagen), which

in German means "people's car". The Chinese name is the literal translation:

大众汽车 - Dàzhòng Qìchē. It sounds completely different but means the same.

You may have heard that especially business relationships can be tricky, and

that in China you only really start negotiations after having had fun at dinner

and drinks. You may also have heard that Chinese ask questions which to

Westerners might seem intrusive or inappropriate.

It is noteworthy that China has not been touched by the oversensitivity which

has lead to political correctness (which is one of the things I absolutely love

about China - Chinese can be very outspoken and call a spade a spade). Be

prepared to be asked whether you are married and have children, and if you

don't, be prepared to be asked why. However. the feeling of Chinese being rude

or intrusive couldn't be farther from the truth. Before returning to this

subject, let's look a little back in history.

Since the times of the Roman Empire, Europe had agreed on the idea that

contracts must be fulfilled, pacta sunt servanda, and for about two

thousand years, there usually was a judiciary in place that you could turn to if

you felt that your rights were not respected. In China, a functioning judiciary

is only a recent phenomenon. During several millennia, if an agreement was not

heeded and you were not in a position of power, you were busted. The only way

you could be safe from being tricked was to get to know your potential business

partner well, before making any commitment. Since Chinese highly value family

relations, it was important to get to know your family background, your ethics,

your trustworthiness. If you were from a family with a low reputation, or if you

claimed to be well-off but hadn't managed to marry and have children, there

might be something wrong with you.

The large dinners and long talks, also about personal things, before the

business negotiations take place, are simply meant to assess whether you are a

good and trustworthy person. Of course, these are the good old days. In regions

where there is new and international business, people have less time. Business

negotiations in Hong Kong, Guangzhou or Shanghai will probably be much less

traditional and more westernized than before. Still, your partners will be happy

if you are and easy and happy guest who enjoys a good meal, drink, and laugh.

People who have never been to China have probably heard that Chinese are

polite, that they will never say "no" and be smiling always. Upon their first

visit to China, they will find out that this is true, albeit only partially -

their hosts, business partners, or colleagues will treat them with utmost

friendliness and hospitality. Once out on the streets, they will experience

people throwing rubbish everywhere, shoving, pushing, jumping queues and

basically ignoring the people around them. Your colleagues will treat you as a

king but they will drive across a zebra crossing without casting a single thought

about the old lady who tries to cross the road with her grandchild.

For a European this is obviously confusing and can in fact be annoying. I

stuck to my rule no. 1: it is their country, and so I resorted to

observing and trying to understand this seemingly irrational behaviour. My

conclusion is this:

For millennia, the population density in China was extremely high compared to

Europe. Around the year 1000, Europe had a a population of about 50 millon

people while in China it was around 100 million. Take into account that in

China, the majority of the population always lived and still lives in the

Eastern part of the country where the land is arable. Around the year 1800,

there were 180 million Europeans and 300 to 400 million Chinese (which was a

third of the world's population at that time).

The higher the population density is, the higher the potential for conflict

and aggression is. A society as populous as the Chinese can only be stable, if

it has developed strategies to minimize potential for conflicts, so that may

serve as an explanation why Chinese will talk around as subject rather than

contradicting you. For a European, this is dishonesty; for a Chinese, it is

being polite and avoiding open conflict.

Now, why do these polite people push and shove? If you have travelled subway

in Europe during rush hour, and if you have a changce to do the same in China,

do carefully observe how people behave: In the subways of Hamburg, the first

people who enter a car will often stand near the doors and block the entrance to

those behind them, although the rest of the car is still almost empty. If you

dare to brush your way past one of these people and only slightly touch them, a

hateful stare will be assured. Now compare this with the subways of Shanghai:

Due to the sheer number of people, there is no way you could avoid brushing past

others, and there are just too many people whom you would have to ask to let you

reach the door - you would never make that in time and so you just push through.

A car is full when no one else fits in. The amazing thing is the complete

absence of any aggressive behaviour. If you bump into someone, nobody cares or

even blinks an eye, everyone understands that bumping into each other is simply

unavoidable.

Long story short: those people you have a relation with will be treated with

utmost politeness and hospitality, and conflicts will be avoided as much as

possible. Those people you don't know and you will never meet again will be

treated as non-existent, which also avoids conflict.

This and more historical exeriences have led to what usually is called the

onion society: The core layer is your family. This were the only people one

could really rely on during famines, wars, natural disasters. Then there is the

layer of personal friends, such as classmates. Next are those you have a sort of

inevitable relationship with, such as neighbours and colleagues. Finally you

have some acquaintances who one could possibly exchance favours with. On the

outside of the onion is the rest of the world, and these don't count because

there are just too many of them.

It is a strategy different to ours, but it has worked well for thousands of

years, and that is what finally counts.

Now I might sound as if I know it all. Well, I guess I have some insight and

ideas about China, and I have made friends in China. But by no means I am an

expert for China. If you want to hear my honest and humble opinion on how to

become an expert for China, that is quite simple:

Move to China and live

there for about four hundred years; then you may call yourself a sage.

Otherwise, be humble, be open-minded, expect everything, and expect

everything to be different from your expectations and prejudices. Try to

understand the reasons behind the things you see, and if you don't understand,

just accept it as it is. After all, it is their country.

home

home China

index

China

index email

email Changshu

Changshu Living

in China

Living

in China